While there remains a strong possibility that I may just be a hopeless romantic or the naive product of a generation that came of age without tasting the bitterness of war, I'll say what I'm going to say here, with the hope that this dose of idealism will find its place among the catacombs of optimism that I believe underly the hearts and minds of everyone who works in this field; or at least anyone who may stumble upon this humble blog.

Across the wooden table at a little stucco-walled cuencan café I listened carefully to a young, bright-eyed french girl, through her viscous accent, as she explained in detail what is wrong with the world and how we are going to change it. I suddenly became conscious of my years when the blunt-edged thought entered my brain: she sounds exactly like me three years ago.

Am I already in the autumn of my idealism? Do we shed our leaves with age, like the deciduous trees, and withdraw into introspective dormancy, with hopes that the bitter winter of cynicism won't heave our roots from the frozen ground and leave us lonely; another rotting log in the springtime forest? I started to doubt myself–was I losing the faith?

Right then I felt safe and warm, in the company of good friends and great ideas, with a cozy blanket of salsa rhythms on the little stereo. But my mind wandered back to a week before, at the same table in the same café, when two thieves came to press their daggers against the window, emitting icy stares through drug-fogged eyes and reminding us all that things are not O.K. The owner rushed to padlock the door and told us that no one could leave until the police came. They never did.

My time here is a series of life lessons. Some come naturally, while others are nearly impossible to digest with my gringo stomach. But what Cuenca keeps whispering to me through all of her beauty and ugliness is that when the day is done, you have your best friends and the people that you love, and that's it.

I come from a place where many people believe in their government, trust the system that engulfs them, rely on the police and public works; where a common faith unites the community with a fair amount of force. But at the same time, it is a place where I have never spoken to my neighbors in our apartment building, although we pass each other on the stairs every day. In that sense, Salt Lake City is the polar opposite of Cuenca.

Before I slipped out of my overcast daydream and actually started focusing on the conversation again, I had to ask myself that pending question: am I making a difference? It kind of burns inside you like that chinese food that you shouldn't have eaten in downtown Quito.

Greed is not easily shed from the human psyche, and although greed for signs of progress in a humanitarian project is distinct from greed for money and power, it still comes from the same family of emotions. I want something for me to make me feel good.

As the date of my return flight draws painfully close, I've taken time to synthesize the bulk of my experience in Ecuador. I've learned that while my greed and impatience will always nip at me, I must learn to read the book of life word for word, page by page–I can't scan through it and arrive to the parts that I find most interesting. Patience and understanding are the keys to progress, along with the obvious prerequisite of hard, hard work. Sometimes it's necessary to go back and re-read a paragraph that you didn't understand in order to understand what comes next.

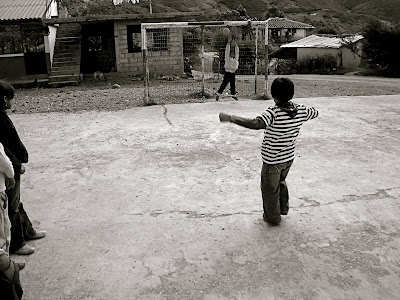

In that sense I've learned to cherish the details: friendships formed with the locals, laughing with the children, the good feeling that comes from even the smallest success and the wisdom that comes with every failure, the beauty of the countryside and even the long, bumpy ride up the hills to Allpacruz that becomes tedious after the 40th time.

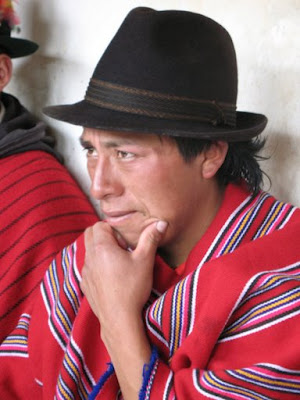

Have I completely fixed what's wrong with the world this summer? No. Have I helped it at least a little bit? I'm pretty certain of that, and I've come to terms with what it takes to make a difference. On my last bus ride, I looked out the window into the poor communities and saw suffering, as I always do. And I felt guilty for my gringo clothes and my gringo money and my privileged lifestyle, like I always do. But something was a little bit different. I felt about 10% less sad, because I knew that I at least represented a tiny part of the struggle to improve the lives of others. And I could relate to them more, because I know something about their reality.

It turns out that I am only in the early springtime of my idealism. This thing is just starting to grow. When people ask me what I'm doing in South America, I'm proud to tell them that I'm working in humanitarian projects with Ascend. I'm proud to be part of the growth of this thing, as it moves forward and makes a difference in more and more lives. And I'm proud of every little struggle, difficulty, mistake, success and achievement that I've experienced this summer, because at the end of the day, I know that we are doing it for the right reason. This is a path that I'm going to continue to follow with my life, and I hope you'll join me. (if you're still reading)

Thank You

Caleb